Heart failure develops when the heart, via an abnormality of cardiac function (detectable or not), fails to pump blood at a rate commensurate with the requirements of the metabolizing tissues or is able to do so only with an elevated diastolic filling pressure.

Essential update: New digoxin use associated with high mortalityIn a community-based cohort study of 2891 digoxin-naive adults with newly diagnosed systolic heart failure, 18% of whom initiated treatment with digoxin, incident digoxin use was associated with significantly higher rates of death (14.2 versus 11.3 per 100 person-years) during a median of 2.5 years of follow-up. Digoxin use was not associated with a significant difference in the risk of hospitalization for heart failure. Results were similar when analyses were stratified by sex and use of beta-blockers.[1, 2, 3] Digoxin currently occupies places in both US and European guidelines as no more than a second-line agent for systolic HF.

Signs and symptomsSigns and symptoms of heart failure include the following:

Exertional dyspnea and/or dyspnea at restOrthopneaAcute pulmonary edemaChest pain/pressure and palpitationsTachycardiaFatigue and weaknessNocturia and oliguriaAnorexia, weight loss, nauseaExophthalmos and/or visible pulsation of eyesDistention of neck veinsWeak, rapid, and thready pulseRales, wheezingS3 gallop and/or pulsus alternansIncreased intensity of P2 heart soundHepatojugular refluxAscites, hepatomegaly, and/or anasarcaCentral or peripheral cyanosis, pallorSee Clinical Presentation for more detail.

DiagnosisHeart failure criteria, classification, and staging

The Framingham criteria for the diagnosis of heart failure consists of the concurrent presence of either 2 major criteria or 1 major and 2 minor criteria.[4]

Major criteria include the following:

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspneaWeight loss of 4.5 kg in 5 days in response to treatmentNeck vein distentionRalesAcute pulmonary edemaHepatojugular refluxS3 gallopCentral venous pressure greater than 16 cm waterCirculation time of 25 secondsRadiographic cardiomegalyPulmonary edema, visceral congestion, or cardiomegaly at autopsyMinor criteria are as follows:

Nocturnal coughDyspnea on ordinary exertionA decrease in vital capacity by one third the maximal value recordedPleural effusionTachycardia (rate of 120 bpm)Bilateral ankle edemaThe New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification system categorizes heart failure on a scale of I to IV,[5] as follows:

Class I: No limitation of physical activityClass II: Slight limitation of physical activityClass III: Marked limitation of physical activityClass IV: Symptoms occur even at rest; discomfort with any physical activityThe American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) staging system is defined by the following 4 stages[6, 7] :

Stage A: High risk of heart failure but no structural heart disease or symptoms of heart failureStage B: Structural heart disease but no symptoms of heart failureStage C: Structural heart disease and symptoms of heart failureStage D: Refractory heart failure requiring specialized interventionsTesting

The following tests may be useful in the initial evaluation for suspected heart failure[6, 8, 9] :

Complete blood count (CBC)UrinalysisElectrolyte levelsRenal and liver function studiesFasting blood glucose levelsLipid profileThyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levelsB-type natriuretic peptide levelsN-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptideElectrocardiographyChest radiography2-dimensional (2-D) echocardiographyNuclear imaging[10] Maximal exercise testingPulse oximetry or arterial blood gasSee Workup for more detail.

ManagementTreatment includes the following:

Nonpharmacologic therapy: Oxygen and noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, dietary sodium and fluid restriction, physical activity as appropriate, and attention to weight gain Pharmacotherapy: Diuretics, vasodilators, inotropic agents, anticoagulants, beta blockers, and digoxinSurgical options

Surgical treatment options include the following:

Electrophysiologic interventionRevascularization proceduresValve replacement/repairVentricular restorationExtracorporeal membrane oxygenationVentricular assist devicesHeart transplantationTotal artificial heartSee Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Image library This chest radiograph shows an enlarged cardiac silhouette and edema at the lung bases, signs of acute heart failure. NextBackground

This chest radiograph shows an enlarged cardiac silhouette and edema at the lung bases, signs of acute heart failure. NextBackgroundHeart failure is the pathophysiologic state in which the heart, via an abnormality of cardiac function (detectable or not), fails to pump blood at a rate commensurate with the requirements of the metabolizing tissues or is able to do so only with an elevated diastolic filling pressure.

Heart failure (see the images below) may be caused by myocardial failure but may also occur in the presence of near-normal cardiac function under conditions of high demand. Heart failure always causes circulatory failure, but the converse is not necessarily the case, because various noncardiac conditions (eg, hypovolemic shock, septic shock) can produce circulatory failure in the presence of normal, modestly impaired, or even supranormal cardiac function. To maintain the pumping function of the heart, compensatory mechanisms increase blood volume, cardiac filling pressure, heart rate, and cardiac muscle mass. However, despite these mechanisms, there is progressive decline in the ability of the heart to contract and relax, resulting in worsening heart failure.

This chest radiograph shows an enlarged cardiac silhouette and edema at the lung bases, signs of acute heart failure.

This chest radiograph shows an enlarged cardiac silhouette and edema at the lung bases, signs of acute heart failure.  A 28-year-old woman presented with acute heart failure secondary to chronic hypertension. The enlarged cardiac silhouette on this anteroposterior (AP) radiograph is caused by acute heart failure due to the effects of chronic high blood pressure on the left ventricle. The heart then becomes enlarged, and fluid accumulates in the lungs (ie, pulmonary congestion).

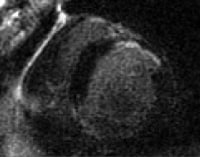

A 28-year-old woman presented with acute heart failure secondary to chronic hypertension. The enlarged cardiac silhouette on this anteroposterior (AP) radiograph is caused by acute heart failure due to the effects of chronic high blood pressure on the left ventricle. The heart then becomes enlarged, and fluid accumulates in the lungs (ie, pulmonary congestion).  This magnetic resonance image shows a scar in the anterior cardiac wall, which may be indicative of a previous myocardial infarction (MI). MIs can precipitate heart failure.

This magnetic resonance image shows a scar in the anterior cardiac wall, which may be indicative of a previous myocardial infarction (MI). MIs can precipitate heart failure. Signs and symptoms of heart failure include tachycardia and manifestations of venous congestion (eg, edema) and low cardiac output (eg, fatigue). Breathlessness is a cardinal symptom of left ventricular (LV) failure that may manifest with progressively increasing severity.

Heart failure can be classified according to a variety of factors (see Heart Failure Criteria and Classification). The New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification for heart failure comprises 4 classes, based on the relationship between symptoms and the amount of effort required to provoke them, as follows[5] :

Class I patients have no limitation of physical activityClass II patients have slight limitation of physical activityClass III patients have marked limitation of physical activityClass IV patients have symptoms even at rest and are unable to carry on any physical activity without discomfortThe American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) heart failure guidelines complement the NYHA classification to reflect the progression of disease and are divided into 4 stages, as follows[6, 7] :

Stage A patients are at high risk for heart failure but have no structural heart disease or symptoms of heart failureStage B patients have structural heart disease but have no symptoms of heart failureStage C patients have structural heart disease and have symptoms of heart failureStage D patients have refractory heart failure requiring specialized interventionsLaboratory studies for heart failure should include a complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, and renal function studies. Imaging studies such as chest radiography and 2-dimensional echocardiography are recommended in the initial evaluation of patients with known or suspected heart failure. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels can be useful in differentiating cardiac and noncardiac causes of dyspnea. (See the Workup Section for more information.)

In acute heart failure, patient care consists of stabilizing the patient's clinical condition; establishing the diagnosis, etiology, and precipitating factors; and initiating therapies to provide rapid symptom relief and survival benefit. Surgical options for heart failure include revascularization procedures, electrophysiologic intervention, cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs), valve replacement or repair, ventricular restoration, heart transplantation, and ventricular assist devices (VADs). (See the Treatment Section for more information.)

The goals of pharmacotherapy are to increase survival and to prevent complications. Along with oxygen, medications assisting with symptom relief include diuretics, digoxin, inotropes, and morphine. Drugs that can exacerbate heart failure should be avoided (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], calcium channel blockers [CCBs], and most antiarrhythmic drugs). (See the Medication Section for more information.)

For further information, see the Medscape Reference articles Pediatric Congestive Heart Failure, Congestive Heart Failure Imaging, Heart Transplantation, Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting, and Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators.

PreviousNextPathophysiologyThe common pathophysiologic state that perpetuates the progression of heart failure is extremely complex, regardless of the precipitating event. Compensatory mechanisms exist on every level of organization, from subcellular all the way through organ-to-organ interactions. Only when this network of adaptations becomes overwhelmed does heart failure ensue.[11, 12, 13, 14, 15]

AdaptationsMost important among the adaptations are the following[16] :

The Frank-Starling mechanism, in which an increased preload helps to sustain cardiac performanceAlterations in myocyte regeneration and deathMyocardial hypertrophy with or without cardiac chamber dilatation, in which the mass of contractile tissue is augmentedActivation of neurohumoral systemsThe release of norepinephrine by adrenergic cardiac nerves augments myocardial contractility and includes activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system [RAAS], the sympathetic nervous system [SNS], and other neurohumoral adjustments that act to maintain arterial pressure and perfusion of vital organs.

In acute heart failure, the finite adaptive mechanisms that may be adequate to maintain the overall contractile performance of the heart at relatively normal levels become maladaptive when trying to sustain adequate cardiac performance.[17]

The primary myocardial response to chronic increased wall stress is myocyte hypertrophy, death/apoptosis, and regeneration.[18] This process eventually leads to remodeling, usually the eccentric type. Eccentric remodeling further worsens the loading conditions on the remaining myocytes and perpetuates the deleterious cycle. The idea of lowering wall stress to slow the process of remodeling has long been exploited in treating heart failure patients.[19]

The reduction of cardiac output following myocardial injury sets into motion a cascade of hemodynamic and neurohormonal derangements that provoke activation of neuroendocrine systems, most notably the above-mentioned adrenergic systems and RAAS.[20]

The release of epinephrine and norepinephrine, along with the vasoactive substances endothelin-1 (ET-1) and vasopressin, causes vasoconstriction, which increases calcium afterload and, via an increase in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), causes an increase in cytosolic calcium entry. The increased calcium entry into the myocytes augments myocardial contractility and impairs myocardial relaxation (lusitropy).

The calcium overload may induce arrhythmias and lead to sudden death. The increase in afterload and myocardial contractility (known as inotropy) and the impairment in myocardial lusitropy lead to an increase in myocardial energy expenditure and a further decrease in cardiac output. The increase in myocardial energy expenditure leads to myocardial cell death/apoptosis, which results in heart failure and further reduction in cardiac output, perpetuating a cycle of further increased neurohumoral stimulation and further adverse hemodynamic and myocardial responses.

In addition, the activation of the RAAS leads to salt and water retention, resulting in increased preload and further increases in myocardial energy expenditure. Increases in renin, mediated by decreased stretch of the glomerular afferent arteriole, reduce delivery of chloride to the macula densa and increase beta1-adrenergic activity as a response to decreased cardiac output. This results in an increase in angiotensin II (Ang II) levels and, in turn, aldosterone levels, causing stimulation of the release of aldosterone. Ang II, along with ET-1, is crucial in maintaining effective intravascular homeostasis mediated by vasoconstriction and aldosterone-induced salt and water retention.

The concept of the heart as a self-renewing organ is a relatively recent development.[21] This new paradigm for myocyte biology has created an entire field of research aimed directly at augmenting myocardial regeneration. The rate of myocyte turnover has been shown to increase during times of pathologic stress.[18] In heart failure, this mechanism for replacement becomes overwhelmed by an even faster increase in the rate of myocyte loss. This imbalance of hypertrophy and death over regeneration is the final common pathway at the cellular level for the progression of remodeling and heart failure.

Ang IIResearch indicates that local cardiac Ang II production (which decreases lusitropy, increases inotropy, and increases afterload) leads to increased myocardial energy expenditure. Ang II has also been shown in vitro and in vivo to increase the rate of myocyte apoptosis.[22] In this fashion, Ang II has similar actions to norepinephrine in heart failure.

Ang II also mediates myocardial cellular hypertrophy and may promote progressive loss of myocardial function. The neurohumoral factors above lead to myocyte hypertrophy and interstitial fibrosis, resulting in increased myocardial volume and increased myocardial mass, as well as myocyte loss. As a result, the cardiac architecture changes, which, in turn, leads to further increase in myocardial volume and mass.

Myocytes and myocardial remodelingIn the failing heart, increased myocardial volume is characterized by larger myocytes approaching the end of their life cycle.[23] As more myocytes drop out, an increased load is placed on the remaining myocardium, and this unfavorable environment is transmitted to the progenitor cells responsible for replacing lost myocytes.

Progenitor cells become progressively less effective as the underlying pathologic process worsens and myocardial failure accelerates. These features—namely, the increased myocardial volume and mass, along with a net loss of myocytes—are the hallmark of myocardial remodeling. This remodeling process leads to early adaptive mechanisms, such as augmentation of stroke volume (Frank-Starling mechanism) and decreased wall stress (Laplace's law), and, later, to maladaptive mechanisms such as increased myocardial oxygen demand, myocardial ischemia, impaired contractility, and arrhythmogenesis.

As heart failure advances, there is a relative decline in the counterregulatory effects of endogenous vasodilators, including nitric oxide (NO), prostaglandins (PGs), bradykinin (BK), atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP). This decline occurs simultaneously with the increase in vasoconstrictor substances from the RAAS and the adrenergic system, which fosters further increases in vasoconstriction and thus preload and afterload. This results in cellular proliferation, adverse myocardial remodeling, and antinatriuresis, with total body fluid excess and worsening of heart failure symptoms.

Systolic and diastolic failureSystolic and diastolic heart failure each result in a decrease in stroke volume. This leads to activation of peripheral and central baroreflexes and chemoreflexes that are capable of eliciting marked increases in sympathetic nerve traffic.

While there are commonalities in the neurohormonal responses to decreased stroke volume, the neurohormone-mediated events that follow have been most clearly elucidated for individuals with systolic heart failure. The ensuing elevation in plasma norepinephrine directly correlates with the degree of cardiac dysfunction and has significant prognostic implications. Norepinephrine, while directly toxic to cardiac myocytes, is also responsible for a variety of signal-transduction abnormalities, such as down-regulation of beta1-adrenergic receptors, uncoupling of beta2-adrenergic receptors, and increased activity of inhibitory G-protein. Changes in beta1-adrenergic receptors result in overexpression and promote myocardial hypertrophy.

ANP and BNPANP and BNP are endogenously generated peptides activated in response to atrial and ventricular volume/pressure expansion. ANP and BNP are released from the atria and ventricles, respectively, and both promote vasodilation and natriuresis. Their hemodynamic effects are mediated by decreases in ventricular filling pressures, owing to reductions in cardiac preload and afterload. BNP, in particular, produces selective afferent arteriolar vasodilation and inhibits sodium reabsorption in the proximal convoluted tubule. It also inhibits renin and aldosterone release and, therefore, adrenergic activation. ANP and BNP are elevated in chronic heart failure. BNP, in particular, has potentially important diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic implications.

For more information, see the Medscape Reference article Natriuretic Peptides in Congestive Heart Failure.

Other vasoactive systemsOther vasoactive systems that play a role in the pathogenesis of heart failure include the ET receptor system, the adenosine receptor system, vasopressin, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha).[24] ET, a substance produced by the vascular endothelium, may contribute to the regulation of myocardial function, vascular tone, and peripheral resistance in heart failure. Elevated levels of ET-1 closely correlate with the severity of heart failure. ET-1 is a potent vasoconstrictor and has exaggerated vasoconstrictor effects in the renal vasculature, reducing renal plasma blood flow, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and sodium excretion.

TNF-alpha has been implicated in response to various infectious and inflammatory conditions. Elevations in TNF-alpha levels have been consistently observed in heart failure and seem to correlate with the degree of myocardial dysfunction. Some studies suggest that local production of TNF-alpha may have toxic effects on the myocardium, thus worsening myocardial systolic and diastolic function.

In individuals with systolic dysfunction, therefore, the neurohormonal responses to decreased stroke volume result in temporary improvement in systolic blood pressure and tissue perfusion. However, in all circumstances, the existing data support the notion that these neurohormonal responses contribute to the progression of myocardial dysfunction in the long term.

Heart failure with normal ejection fractionIn diastolic heart failure (heart failure with normal ejection fraction [HFNEF]), the same pathophysiologic processes occur that lead to decreased cardiac output in systolic heart failure, but they do so in response to a different set of hemodynamic and circulatory environmental factors that depress cardiac output.[25]

In HFNEF, altered relaxation and increased stiffness of the ventricle (due to delayed calcium uptake by the myocyte sarcoplasmic reticulum and delayed calcium efflux from the myocyte) occur in response to an increase in ventricular afterload (pressure overload). The impaired relaxation of the ventricle then leads to impaired diastolic filling of the left ventricle (LV).

Morris et al found that RV subendocardial systolic dysfunction and diastolic dysfunction, as detected by echocardiographic strain rate imaging, are common in patients with HFNEF. This dysfunction is potentially associated with the same fibrotic processes that affect the subendocardial layer of the LV and, to a lesser extent, with RV pressure overload. This may play a role in the symptomatology of patients with HFNEF.[26]

LV chamber stiffnessAn increase in LV chamber stiffness occurs secondary to any one of, or any combination of, the following 3 mechanisms:

Rise in filling pressureShift to a steeper ventricular pressure-volume curveDecrease in ventricular distensibilityA rise in filling pressure is the movement of the ventricle up along its pressure-volume curve to a steeper portion, as may occur in conditions such as volume overload secondary to acute valvular regurgitation or acute LV failure due to myocarditis.

A shift to a steeper ventricular pressure-volume curve results, most commonly, not only from increased ventricular mass and wall thickness (as observed in aortic stenosis and long-standing hypertension) but also from infiltrative disorders (eg, amyloidosis), endomyocardial fibrosis, and myocardial ischemia.

Parallel upward displacement of the diastolic pressure-volume curve is generally referred to as a decrease in ventricular distensibility. This is usually caused by extrinsic compression of the ventricles.

Concentric LV hypertrophyPressure overload that leads to concentric LV hypertrophy (LVH), as occurs in aortic stenosis, hypertension, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, shifts the diastolic pressure-volume curve to the left along its volume axis. As a result, ventricular diastolic pressure is abnormally elevated, although chamber stiffness may or may not be altered.

Increases in diastolic pressure lead to increased myocardial energy expenditure, remodeling of the ventricle, increased myocardial oxygen demand, myocardial ischemia, and eventual progression of the maladaptive mechanisms of the heart that lead to decompensated heart failure.

ArrhythmiasWhile life-threatening rhythms are more common in ischemic cardiomyopathy, arrhythmia imparts a significant burden in all forms of heart failure. In fact, some arrhythmias even perpetuate heart failure. The most significant of all rhythms associated with heart failure are the life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. Structural substrates for ventricular arrhythmias that are common in heart failure, regardless of the underlying cause, include ventricular dilatation, myocardial hypertrophy, and myocardial fibrosis.

At the cellular level, myocytes may be exposed to increased stretch, wall tension, catecholamines, ischemia, and electrolyte imbalance. The combination of these factors contributes to an increased incidence of arrhythmogenic sudden cardiac death in patients with heart failure.

PreviousNextEtiologyMost patients who present with significant heart failure do so because of an inability to provide adequate cardiac output in that setting. This is often a combination of the causes listed below in the setting of an abnormal myocardium. The list of causes responsible for presentation of a patient with heart failure exacerbation is very long, and searching for the proximate cause to optimize therapeutic interventions is important.

From a clinical standpoint, classifying the causes of heart failure into the following 4 broad categories is useful:

Underlying causes: Underlying causes of heart failure include structural abnormalities (congenital or acquired) that affect the peripheral and coronary arterial circulation, pericardium, myocardium, or cardiac valves, thus leading to increased hemodynamic burden or myocardial or coronary insufficiency Fundamental causes: Fundamental causes include the biochemical and physiologic mechanisms, through which either an increased hemodynamic burden or a reduction in oxygen delivery to the myocardium results in impairment of myocardial contraction Precipitating causes: Overt heart failure may be precipitated by progression of the underlying heart disease (eg, further narrowing of a stenotic aortic valve or mitral valve) or various conditions (fever, anemia, infection) or medications (chemotherapy, NSAIDs) that alter the homeostasis of heart failure patients Genetics of cardiomyopathy: Dilated, arrhythmic right ventricular and restrictive cardiomyopathies are known genetic causes of heart failure. Underlying causesSpecific underlying factors cause various forms of heart failure, such as systolic heart failure (most commonly, left ventricular systolic dysfunction), heart failure with preserved LVEF, acute heart failure, high-output heart failure, and right heart failure.

Underlying causes of systolic heart failure include the following:

Coronary artery diseaseDiabetes mellitusHypertensionValvular heart disease (stenosis or regurgitant lesions)Arrhythmia (supraventricular or ventricular)Infections and inflammation (myocarditis)Peripartum cardiomyopathyCongenital heart diseaseDrugs (either recreational, such as alcohol and cocaine, or therapeutic drugs with cardiac side effects, such as doxorubicin)Idiopathic cardiomyopathyRare conditions (endocrine abnormalities, rheumatologic disease, neuromuscular conditions)Underlying causes of diastolic heart failure include the following:

Coronary artery diseaseDiabetes mellitusHypertensionValvular heart disease (aortic stenosis)Hypertrophic cardiomyopathyRestrictive cardiomyopathy (amyloidosis, sarcoidosis)Constrictive pericarditisUnderlying causes of acute heart failure include the following:

Acute valvular (mitral or aortic) regurgitationMyocardial infarctionMyocarditisArrhythmiaDrugs (eg, cocaine, calcium channel blockers, or beta-blocker overdose)SepsisUnderlying causes of high-output heart failure include the following:

AnemiaSystemic arteriovenous fistulasHyperthyroidismBeriberi heart diseasePaget disease of boneAlbright syndrome (fibrous dysplasia)Multiple myelomaPregnancyGlomerulonephritisPolycythemia veraCarcinoid syndromeUnderlying causes of right heart failure include the following:

Left ventricular failureCoronary artery disease (ischemia)Pulmonary hypertensionPulmonary valve stenosisPulmonary embolismChronic pulmonary diseaseNeuromuscular diseasePrecipitating causes of heart failureA previously stable, compensated patient may develop heart failure that is clinically apparent for the first time when the intrinsic process has advanced to a critical point, such as with further narrowing of a stenotic aortic valve or mitral valve. Alternatively, decompensation may occur as a result of failure or exhaustion of the compensatory mechanisms but without any change in the load on the heart in patients with persistent, severe pressure or volume overload. In particular, consider whether the patient has underlying coronary artery disease or valvular heart disease.

The most common cause of decompensation in a previously compensated patient with heart failure is inappropriate reduction in the intensity of treatment, such as dietary sodium restriction, physical activity reduction, or drug regimen reduction. Uncontrolled hypertension is the second most common cause of decompensation, followed closely by cardiac arrhythmias (most commonly, atrial fibrillation). Arrhythmias, particularly ventricular arrhythmias, can be life threatening. Also, patients with one form of underlying heart disease that may be well compensated can develop heart failure when a second form of heart disease ensues. For example, a patient with chronic hypertension and asymptomatic LVH may be asymptomatic until a myocardial infarction (MI) develops and precipitates heart failure.

Systemic infection or the development of unrelated illness can also lead to heart failure. Systemic infection precipitates heart failure by increasing total metabolism as a consequence of fever, discomfort, and cough, increasing the hemodynamic burden on the heart. Septic shock, in particular, can precipitate heart failure by the release of endotoxin-induced factors that can depress myocardial contractility.

Cardiac infection and inflammation can also endanger the heart. Myocarditis or infective endocarditis may directly impair myocardial function and exacerbate existing heart disease. The anemia, fever, and tachycardia that frequently accompany these processes are also deleterious. In the case of infective endocarditis, the additional valvular damage that ensues may precipitate cardiac decompensation.

Patients with heart failure, particularly when confined to bed, are at high risk of developing pulmonary emboli, which can increase the hemodynamic burden on the right ventricle by further elevating right ventricular (RV) systolic pressure, possibly causing fever, tachypnea, and tachycardia.

Intense, prolonged physical exertion or severe fatigue, such as may result from prolonged travel or emotional crisis, is a relatively common precipitant of cardiac decompensation. The same is true of exposure to severe climate change (ie, the individual comes in contact with a hot, humid environment or a bitterly cold one).

Excessive intake of water and/or sodium and the administration of cardiac depressants or drugs that cause salt retention are other factors that can lead to heart failure.

Because of increased myocardial oxygen consumption and demand beyond a critical level, the following high-output states can precipitate the clinical presentation of heart failure:

Profound anemiaThyrotoxicosisMyxedemaPaget disease of boneAlbright syndromeMultiple myelomaGlomerulonephritisCor pulmonalePolycythemia veraObesityCarcinoid syndromePregnancyNutritional deficiencies (eg, thiamine deficiency, beriberi)Longitudinal data from the Framingham Heart Study suggests that antecedent subclinical left ventricular systolic or diastolic dysfunction is associated with an increased incidence of heart failure, supporting the notion that heart failure is a progressive syndrome.[27, 28] Another analysis of over 36,000 patients undergoing outpatient echocardiography reported that moderate or severe diastolic dysfunction, but not mild diastolic dysfunction, is an independent predictor of mortality.[29]

Genetics of cardiomyopathyAutosomal dominant inheritance has been demonstrated in dilated cardiomyopathy and in arrhythmic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Restrictive cardiomyopathies are usually sporadic and associated with the gene for cardiac troponin I. Genetic tests are available at major genetic centers for cardiomyopathies.[30]

In families with a first-degree relative who has been diagnosed with a cardiomyopathy leading to heart failure, the at-risk patient should be screened and followed.[30] The recommended screening consists of an electrocardiogram and an echocardiogram. If the patient has an asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction, it should be treated.[30]

PreviousNextEpidemiologyUnited States statisticsAccording to the American Heart Association, heart failure affects nearly 5.7 million Americans of all ages[31] and is responsible for more hospitalizations than all forms of cancer combined. It is the number 1 cause of hospitalization for Medicare patients. With improved survival of patients with acute myocardial infarction and with a population that continues to age, heart failure will continue to increase in prominence as a major health problem in the United States.[32, 33, 34, 35]

Analysis of national and regional trends in hospitalization and mortality among Medicare beneficiaries from 1998-2008 showed a relative decline of 29.5% in heart failure hospitalizations[36] ; however, wide variations are noted between states and races, with black men having the slowest rate of decline. A relative decline of 6.6% in mortality was also observed, although the rate was uneven across states. The length of stay decreased from 6.8 days to 6.4 days, despite an overall increase in the comorbid conditions.[36]

Heart failure statistics for the United States are as follows:

Heart failure is the fastest-growing clinical cardiac disease entity in the United States, affecting 2% of the populationHeart failure accounts for 34% of cardiovascular-related deaths[31] Approximately 670,000 new cases of heart failure are diagnosed each year[31] About 277,000 deaths are caused by heart failure each year[31] Heart failure is the most frequent cause of hospitalization in patients older than 65 years, with an annual incidence of 10 per 1,000[31] Rehospitalization rates during the 6 months following discharge are as much as 50%[37] Nearly 2% of all hospital admissions in the United States are for decompensated heart failure, and the average duration of hospitalization is about 6 days In 2010, the estimated total cost of heart failure in the United States was $39.2 billion,[38] representing 1-2% of all health care expendituresThe incidence and prevalence of heart failure are higher in blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans, and recent immigrants from developing nations, Russia, and the former Soviet republics. The higher prevalence of heart failure in blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans is directly related to the higher incidence and prevalence of hypertension and diabetes. This problem is particularly exacerbated by a lack of access to health care and by substandard preventive health care available to the most indigent of individuals in these and other groups; in addition, many persons in these groups do not have adequate health insurance.

The higher incidence and prevalence of heart failure in recent immigrants from developing nations are largely due to a lack of prior preventive health care, a lack of treatment, or substandard treatment for common conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, rheumatic fever, and ischemic heart disease.

Men and women have the same incidence and the same prevalence of heart failure. However, there are still many differences between men and women with heart failure, such as the following:

Women tend to develop heart failure later in life than men doWomen are more likely than men to have preserved systolic functionWomen develop depression more commonly than men doWomen have signs and symptoms of heart failure similar to those of men, but they are more pronounced in womenWomen survive longer with heart failure than men doThe prevalence of heart failure increases with age. The prevalence is 1-2% of the population younger than 55 years and increases to a rate of 10% for persons older than 75 years. Nonetheless, heart failure can occur at any age, depending on the cause.

International statisticsHeart failure is a worldwide problem. The most common cause of heart failure in industrialized countries is ischemic cardiomyopathy, with other causes, including Chagas disease and valvular cardiomyopathy, assuming a more important role in developing countries. However, in developing nations that have become more urbanized and more affluent, eating a more processed diet and leading a more sedentary lifestyle have resulted in an increased rate of heart failure, along with increased rates of diabetes and hypertension. This change was illustrated in a population study in Soweto, South Africa, where the community transformed into a more urban and westernized city, followed by an increase in diabetes, hypertension, and heart failure.[39]

In terms of treatment, one study showed few important differences in uptake of key therapies in European countries with widely differing cultures and varying economic status for patients with heart failure. In contrast, studies of sub-Saharan Africa, where health care resources are more limited, have shown poor outcomes in specific populations.[40, 41] For example, in some countries, hypertensive heart failure carries a 25% 1-year mortality rate, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–associated cardiomyopathy generally progresses to death within 100 days of diagnosis in patients who are not treated with antiretroviral drugs.

While data regarding developing nations are not as robust as studies of Western society, the following trends in developing nations are apparent:

Causes tend to be largely nonischemicPatients tend to present at a younger ageOutcomes are largely worse where health care resources are limitedIsolated right heart failure tends to be more prominent, with a variety of causes having been postulated, ranging from tuberculous pericardial disease to lung disease and pollution PreviousNextPrognosisIn general, the mortality following hospitalization for patients with heart failure is 10.4% at 30 days, 22% at 1 year, and 42.3% at 5 years, despite marked improvement in medical and device therapy.[31, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46] Each rehospitalization increases mortality by about 20-22%.[31]

Mortality is greater than 50% for patients with NYHA class IV, ACC/AHA stage D heart failure. Heart failure associated with acute MI has an inpatient mortality of 20-40%; mortality approaches 80% in patients who are also hypotensive (eg, cardiogenic shock). (See Heart Failure Criteria and Classification).

Numerous demographic, clinical and biochemical variables have been reported to provide important prognostic value in patients with heart failure, and several predictive models have been developed.[47]

A study by van Diepen et al suggests that patients with heart failure or atrial fibrillation have a significantly higher risk of noncardiac postoperative mortality than patients with coronary artery disease; this risk should be considered even if a minor procedure is planned.[48]

A study by Bursi et al found that among community patients with heart failure, pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP), assessed by Doppler echocardiography, can strongly predict death and can provide incremental and clinically significant prognostic information independent of known outcome predictors.[49]

Higher concentrations of galectin-3, a marker of cardiac fibrosis, were associated with an increased risk for incident heart failure (hazard ratio: 1.28 per 1 SD increase in log galectin-3) in the Framingham Offspring Cohort. Galectin-3 was also associated with an increased risk for all-cause mortality (multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio: 1.15).[50]

PreviousNextPatient EducationTo help prevent recurrence of heart failure in patients in whom heart failure was caused by dietary factors or medication noncompliance, counsel and educate such patients about the importance of proper diet and the necessity of medication compliance. Dunlay et al examined medication use and adherence among community-dwelling patients with heart failure and found that medication adherence was suboptimal in many patients, often because of cost.[51] A randomized controlled trial of 605 patients with heart failure reported that the incidence of all-cause hospitalization or death was not reduced in patients receiving multi-session self-care training compared to those receiving a single session intervention. The optimum method for patient education remains to be established. It appears that more intensive interventions are not necessarily better.[52]

For patient education information, see the Heart Health Center, Cholesterol Center, and Diabetes Center, as well as Congestive Heart Failure, High Cholesterol, Chest Pain, Heart Rhythm Disorders, Coronary Heart Disease, and Heart Attack.

PreviousProceed to Clinical Presentation , Heart Failure

0 comments:

Post a Comment