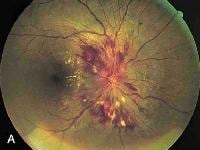

A hypertensive emergency is a condition in which elevated blood pressure results in target organ damage. The systems primarily involved include the central nervous system, the cardiovascular system, and the renal system. Malignant hypertension and accelerated hypertension are both hypertensive emergencies, with similar outcomes and therapies. In order to diagnose malignant hypertension, papilledema (as seen in the image below) must be present.[1]

Papilledema. Note the swelling of the optic disc, with blurred margins.

Papilledema. Note the swelling of the optic disc, with blurred margins. Up to 1% of patients with essential hypertension develop malignant hypertension, but the reason some patients develop malignant hypertension whereas others do not is unknown. The characteristic vascular lesion is fibrinoid necrosis of arterioles and small arteries, which causes the clinical manifestations of end-organ damage. Red blood cells are damaged as they flow through vessels obstructed by fibrin deposition, resulting in microangiopathic hemolytic anemia.

Another pathologic process is the dilatation of cerebral arteries following a breakthrough of the normal autoregulation of cerebral blood flow. Under normal conditions, cerebral blood flow is kept constant by cerebral vasoconstriction in response to increases in blood pressure. In patients without hypertension, flow is kept constant over a mean pressure of 60-120 mm Hg. In patients with hypertension, flow is constant over a mean pressure of 110-180 mm Hg because of arteriolar thickening. When blood pressure is raised above the upper limit of autoregulation, arterioles dilate. This results in hyperperfusion and cerebral edema, which cause the clinical manifestations of hypertensive encephalopathy.

Other causes of malignant hypertension include any form of secondary hypertension; complications of pregnancy; use of cocaine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), or oral contraceptives; and the withdrawal of alcohol, beta-blockers, or alpha-stimulants. Renal artery stenosis, pheochromocytoma (most pheochromocytomas can be localized using computed tomography (CT) scanning of the adrenals), aortic coarctation, and hyperaldosteronism are also secondary causes of hypertension. In addition, both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism can cause hypertension.

The following conditions should also be considered when making the diagnosis: stroke, intracranial mass, head injury, epilepsy or postictal state, connective-tissue disease (especially lupus with cerebral vasculitis), drug overdose or withdrawal, cocaine or amphetamine ingestion, acute anxiety, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.[2]

For more information, see Hypertension.

Accelerated hypertension and hypertensive urgencyAccelerated hypertension is defined as a recent significant increase over baseline blood pressure that is associated with target organ damage. This is usually seen as vascular damage on funduscopic examination, such as flame-shaped hemorrhages or soft exudates, but without papilledema.

Hypertensive urgency must be distinguished from hypertensive emergency. Urgency is defined as severely elevated blood pressure (ie, systolic >220 mm Hg or diastolic >120 mm Hg) with no evidence of target organ damage.

Hypertensive emergencies require immediate therapy to decrease blood pressure within minutes to hours.[3] In contrast, no evidence suggests a benefit from rapidly reducing blood pressure in patients with hypertensive urgency. In fact, such aggressive therapy may harm the patient, resulting in cardiac, renal, or cerebral hypoperfusion. This article discusses hypertensive emergency, but therapy for hypertensive urgency is discussed briefly.

Patient educationPatients must be taught an appropriate diet for long-term management, and upon discharge, patients should not only know the signs and symptoms that should prompt immediate notification of a physician but also know the proper dosing and adverse effects of their medications.

For excellent patient education resources, visit eMedicineHealth's Diabetes Center. Also, see eMedicineHealth's patient education article High Blood Pressure.

For more information, see Hypertension.

NextEvaluationThe history should include screening for symptoms of malignant hypertension, focusing on the cardiac, renal, and central nervous systems. Underlying medical disorders should be reviewed, including the possibility of eclampsia. The patient's medications and other drugs should be thoroughly reviewed[4] ; agents that may cause a hypertensive emergency include cocaine, MAOIs, and oral contraceptives; the withdrawal of beta-blockers, alpha-stimulants (eg, clonidine), or alcohol also may cause hypertensive emergency.

In one review, the most common presentations of hypertensive emergencies at an emergency department were chest pain (27%), dyspnea (22%), and neurologic deficit (21%).

A thorough physical examination should be conducted, with the focus on the cardiovascular and central nervous systems and on the retinal examination.

Cardiovascular systemThe cardiac presentation of malignant hypertension is angina and/or myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or pulmonary edema. Orthostatic symptoms may be prominent.

The heart's initial response to systemic hypertension is to develop concentric left ventricular hypertrophy. Eventually, the left ventricle becomes dilatated. This is reflected on physical examination by a fourth heart sound initially, followed by the typical changes of dilated cardiomyopathy.

Blood pressure must be checked in both arms to screen for aortic dissection or coarctation. If coarctation is suspected, blood pressure also should be measured in the legs. Furthermore, screen for carotid or renal bruits; palpate the precordium, looking for sustained left ventricular lift; and auscultate for a third or fourth heart sound or murmurs.

The patient's volume status must also be assessed with orthostatic vital signs, examination of the jugular veins, assessment of the liver size, and investigation for peripheral edema and pulmonary rales.

Central nervous systemNeurologic presentations are occipital headache, cerebral infarction or hemorrhage, visual disturbance, or hypertensive encephalopathy (a symptom complex of severe hypertension, headache, vomiting, visual disturbance, mental status changes, seizure, and retinopathy with papilledema). Focal signs and symptoms are uncommon and may indicate another process, such as cerebral infarct or hemorrhage.

A complete neurologic examination is needed to screen for localizing signs. Note that focal neurologic signs might not be attributable to encephalopathy; focal signs mandate screening for cerebral hemorrhage, infarct, or the presence of a mass.

Renal, gastrointestinal, and ophthalmologic systemsRenal disease may present as oliguria or any of the typical features of renal failure. Gastrointestinal symptoms are nausea and vomiting; in addition, diffuse arteriolar damage can result in microangiopathic hemolytic anemia.

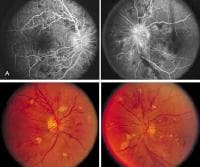

Patients may complain of blurred vision. A funduscopic examination may reveal flame-shaped retinal hemorrhages, soft exudates, or papilledema (see the following images).[5]

Hypertensive retinopathy. Note the flame-shaped hemorrhages, soft exudates, and early disc blurring. PreviousNextDifferential Diagnosis

Hypertensive retinopathy. Note the flame-shaped hemorrhages, soft exudates, and early disc blurring. PreviousNextDifferential DiagnosisAcute Renal Failure

Aortic Coarctation

Aortic Dissection

Chronic Renal Failure

Eclampsia

Hypercalcemia

Hyperthyroidism

Pheochromocytoma

Renal Artery Stenosis

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

PreviousNextWorkup for Malignant HypertensionLaboratory studiesInitial laboratory studies include a complete blood cell (CBC) count and electrolytes (including calcium), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, glucose, coagulation profile, and urinalysis. Other laboratory studies are indicated only as directed by the initial workup. These may include measurements for cardiac enzymes, urinary catecholamines, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and 24-hour urine collection for vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) and catecholamines.

Renal function should be evaluated through urinalysis, complete chemistry profile, and CBC count. Expected findings include elevated BUN and creatinine, hyperphosphatemia, hyperkalemia or hypokalemia, glucose abnormalities, acidosis, hypernatremia, and evidence of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and azotemic oliguric renal failure. Urinalysis may reveal proteinuria, microscopic hematuria, and red blood cell or hyaline casts.

Diffuse intrarenal ischemia results in increased levels of plasma renin, angiotensin II, and aldosterone, with resulting hypovolemia and hypokalemia. Sodium depletion is common and may be severe.[6]

Radiologic studiesRoutine screening consists of a chest radiograph, which is useful for assessment of cardiac enlargement, pulmonary edema, or involvement of other thoracic structures, such as rib notching with aortic coarctation or a widened mediastinum with aortic dissection. Other studies, such as head CT scanning, transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), and renal angiography, are indicated only as directed by the initial workup.

ElectrocardiographyAn ECG is an essential part of the evaluation to screen for ischemia, infarct, or evidence of electrolyte abnormalities or drug overdose. In the earliest stages of malignant hypertension, electrocardiogram and echocardiogram reveal left atrial enlargement and left ventricular hypertrophy.

PreviousNextMedical ManagementPatients with malignant hypertension are usually admitted to an intensive care unit for continuous cardiac monitoring, frequent assessment of neurologic status and urine output, and administration of intravenous antihypertensive medications and fluids. Patients typically have altered blood pressure autoregulation, and overzealous reduction of blood pressure to reference range levels may result in organ hypoperfusion.

In patients with stroke, cardiac compromise, or renal failure, appropriate consultation should be considered. In institutions with specialists in hypertension, prompt consultation may improve the overall control of blood pressure.

Hypertensive urgencies do not mandate admission to a hospital. The goal of therapy is with these cases is to reduce blood pressure within 24 hours, which can be achieved as an outpatient.

For more information, see Hypertension.

PharmacotherapyThe initial goal of therapy is to reduce the mean arterial pressure by approximately 25% over the first 24-48 hours. An intra-arterial line is helpful for continuous monitoring of blood pressure. Sodium and volume depletion may be severe, and volume expansion with isotonic sodium chloride solution must be considered.[3] Secondary causes of hypertension should be investigated.

No trials exist comparing the efficacy of various agents in the treatment of malignant hypertension. Drugs are chosen based on their rapidity of action, ease of use, special situations, and convention.

The most commonly used intravenous drug is nitroprusside. An alternative for patients with renal insufficiency is intravenous fenoldopam. Labetalol is another common alternative, providing easy transition from intravenous to oral dosing. However, a trial by Peacock et al demonstrated that intravenous calcium blockers (eg, nicardipine) could be useful in quickly and safely reducing blood pressure to target levels and seemed more effective than intravenous labetalol.[7]

Beta-blockade can be accomplished intravenously with esmolol or metoprolol. Also available parenterally are diltiazem, verapamil, and enalapril. Hydralazine is reserved for use in pregnant patients, whereas phentolamine is the drug of choice for a pheochromocytoma crisis. Oral medications should be initiated as soon as possible in order to ease transition to an outpatient setting.

Diet and ActivityIn patients with stroke, cardiac compromise, or renal failure, appropriate consultation should be considered. In institutions with specialists in hypertension, prompt consultation may improve the overall control of blood pressure.

Activity is limited to bedrest until the patient is stable. Patients should be able to resume normal activity as outpatients once their blood pressure has been controlled.

ComplicationsOverzealous reduction of blood pressure can result in organ hypoperfusion, and target organ damage can be missed without a thorough evaluation. Note that enalapril has an unpredictable response in hypovolemic patients, with a possible uncontrolled drop in blood pressure.

Special ConcernsProperly diagnosing hypertensive emergency and urgency is essential to proper triage and treatment; however, reducing blood pressure too rapidly can result in patient harm. In addition, all patients should be carefully assessed for secondary causes of hypertension, and upon discharge, patients should have close follow-up care. They should know the signs and symptoms that necessitate immediate notification of a physician.

PreviousNextSurgical TherapyA therapy under clinical trial involving implantation of a carotid baroreflex stimulator has shown some promising results.[8]

Initially, patients treated for malignant hypertension are instructed to fast until stable. Once stable, all patients should obtain good long-term care of their hypertension, including a diet that is low in salt. If indicated, the patient should follow a diet that can induce weight loss.

For more information, see Hypertension.

PreviousNextPrognosis and PreventionIn a retrospective analysis of 197 patients with malignant hypertension, Gonzalez et al found that 5 and 10 years after presentation, the chances of renal survival were 84% and 72%, respectively.[9] The investigators examined data from patients diagnosed between 1974 and 2007 and reported predictors of renal outcome included whether or not the patient was diagnosed between 1974 and 1985, the existence of previous chronic renal impairment, the degree of proteinuria and the amount of renal function at baseline, the presence of microhematuria, systolic and diastolic blood pressure values, and the proteinuria value during follow-up.[9] However, after multivariate analysis, the only significant risk factor was found to be the mean proteinuria value during follow-up.[9] At 5 and 10 years after presentation, the chances of renal survival in patients with a mean proteinuria value less than 0.5 g/24 h were 100% and 95%, respectively.[9]

Before the advent of effective therapy, the life expectancy of those affected by malignant hypertension was less than 2 years, with most deaths resulting from stroke, renal failure, or heart failure. The survival rate at 1 year was less than 25%, and at 5 years, it was less than 1%. However, with current therapy, including dialysis, the survival rate at 1 year is greater than 90%, and at 5 years, it is 80%. The most common cause of death is cardiovascular, with stroke and renal failure also common.

A British study that examined survival statistics over the course of 40 years in patients with malignant hypertension found an even higher 5-year survival rate.[10] Reviewing information from 446 patients with malignant hypertension, the authors determined that before 1977, the 5-year survival rate was 32%, whereas for patients who were diagnosed between 1997 and 2006, the 5-year rate was 91%. The investigators suggested that the change was associated with lower targets for and tighter control of patients' blood pressure, along with the availability of additional classes of antihypertensive medications.[10] The authors also found age, baseline creatinine level, and follow-up systolic blood pressure to be independent predictors of survival.

PreventionThe best way to prevent further episodes of hypertensive emergencies is to ensure that the patient has close outpatient follow-up for hypertension treatment. This can usually be accomplished by a general medicine or family practice physician, but referral to a hypertension specialist should also be considered for patients who require complex drug therapy or additional secondary workup.

Previous, Malignant Hypertension

0 comments:

Post a Comment